Church / Public Commissions

Working on projects for churches, synagogues and temples, schools and public buildings starts with a fundamental assumption, that I must listen well to my clients. Sometimes, it can be a lengthy process.

Working on projects for churches, synagogues and temples, schools and public buildings starts with a fundamental assumption, that I must listen well to my clients. Sometimes, it can be a lengthy process.

If it is a vestry committe or a board of trustees or any other group charged with deciding what the art should contribute to a place of study or worship, every voice needs to be heard, and every idea put forward needs to be given serious consideration.

Working for the Good Shepherd Episcopal Church of Barre, Vermont, comes to mind as an example of what I mean.

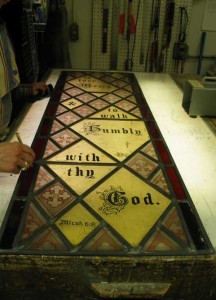

The original idea (the church vestry and art comittee’s) was to remove a crumbling old diamondpane window from the front of the church and to substitute a new window. The window in question was a “triple lancet Gothic” style, about ten feet wide and thirteen high, located high above the front doors in the back of the nave. The new window was to be called “Genesis,” and would feature a dove. That part was easy. But, what design? Dove going up? Going Down? With or without olive branch? Every voice was heard. No consensus was reached. I drew six or seven versions, small dove in the middle window. large dove with its wings spread across all three panels. The process dragged out for nearly a year. Everybody was patient!

What I as an artist bring to the table is a full understanding of my medium. That means, in my mind, that I know my materials and techniques, I know the engineering and technical requirements, and I have to have a pretty good idea of how light and color will work in any given setting. But this project involved a lot of give-and take, and everybody involved learned from everybody else. Above all, we listened to each other.

What I as an artist bring to the table is a full understanding of my medium. That means, in my mind, that I know my materials and techniques, I know the engineering and technical requirements, and I have to have a pretty good idea of how light and color will work in any given setting. But this project involved a lot of give-and take, and everybody involved learned from everybody else. Above all, we listened to each other.

One day, the project took wings. A member of the committe walked into a meeting with an image she’d found in a scientific journal showing a beautiful mathematical graph of something called a “Cosmic Strange Attractor”. It came out of the work of Ilya Prigogine, a Nobel-Prize winning Chemist who had turned to mathematics as a second career. It appealed to everybody, and then ideas flowed thick and fast. Someone thought of running out the gothic top lines down into the bottom. Someone else thought of the Big Bang (“Let There Be Light!”) and we added sandblasted cosmic rays to the design. I remembered how the Tiffany windows that I’d worked on over the years had included a technique called “Plating” which adds layers of stained glass together to give deep and complex effects of light and color. The “Dove”, which is what we still call it, ultimately was made of a top layer of corrugated, ripply Irridescent glass pieces over second and third layers which included kiln-fired frit. A local glass artist who’d once been my student offered his firing expertise and the use of his big kiln, much bigger than mine. The lower sections of the window included grapevines, because every other window in the church has a vineyard theme.

One day, the project took wings. A member of the committe walked into a meeting with an image she’d found in a scientific journal showing a beautiful mathematical graph of something called a “Cosmic Strange Attractor”. It came out of the work of Ilya Prigogine, a Nobel-Prize winning Chemist who had turned to mathematics as a second career. It appealed to everybody, and then ideas flowed thick and fast. Someone thought of running out the gothic top lines down into the bottom. Someone else thought of the Big Bang (“Let There Be Light!”) and we added sandblasted cosmic rays to the design. I remembered how the Tiffany windows that I’d worked on over the years had included a technique called “Plating” which adds layers of stained glass together to give deep and complex effects of light and color. The “Dove”, which is what we still call it, ultimately was made of a top layer of corrugated, ripply Irridescent glass pieces over second and third layers which included kiln-fired frit. A local glass artist who’d once been my student offered his firing expertise and the use of his big kiln, much bigger than mine. The lower sections of the window included grapevines, because every other window in the church has a vineyard theme.

Designing it took thirteen months, building and installing it took less than four. Two people were married in the church beneath our window the day after we finished it, right after the scaffolding came down. Let there be Light!